In this subchapter, curator Devorah Romanek investigates the hidden and not-so-hidden correlations between colonization around the world and the spread of disease. Digging further, she observes the manner in which this history might be found, explicitly or implicitly, in museum, library and archive collections. This is a complex story, and if you want to move through it more quickly and skip details, read just the text in bold.

Colonization, Disease, Museums: A Global Story

Chapters on Sickness

Memory in Athens

A History of Epidemics

Colonization

Scientific Modeling

The pairing of objects with stories within this essay is an initial attempt to begin to unearth connections between sickness, colonialism and museums.

You can click on the thumbnails just below to go directly to the full image and caption.You can also scroll through the subchapter to see the images.

Introduction

Believe by Chip Thomas, artist and medical doctor, and Esther Belin, both of the Navajo Nation, June 2020, installed on the Navajo Nation. From the series in process “Hope to See you on the Other Side.” The collaborative project, founded by Thomas in April 2020 is a response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Thomas asked collaborators to reflect on the pandemic and what they envision afterwards. A digital zine and various installations will be the end result. The other artists include: Jess X Snow, Mahogany L. Browne, Ursula Rucker, Sonia Sanchez, André Leon Gray and Titus Brooks Heagins. Image: Chip Thomas

Covid-19 has been spreading in the Americas since January 15th of 2020, as far as is known, when a young man returned to Washington State from Wuhan China, where the virus originated, (The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020 b). The disease was first reported in South America on February 26th in São Paulo, Brazil (Call 2020). On March 6th, Costa Rica became the first country in Central America to report a case in a tourist visiting from the United States (Horwitz, et al. 2020). Throughout the Americas, Indigenous peoples, and other people of color and minority groups are suffering disproportionally from both infection and death from the disease (see, for example: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020, Hidalgo et al 2020, Mineo 2020, Nelson 2020).

This story is set against the backdrop of a long history of the global spread of disease and its relation to imperial expansion and colonization. Of course, diseases and their spread within and between human populations has been present wherever people have dwelled. However, beginning with the “Age of Exploration” in the 15th and 16th centuries, Europeans set out on overseas voyages spurred on by ambition (King 2013: 121) and a desire to find new trade routes and resources. They brought with them pathogens that those they encountered had little to no resistance to: “The introduction of novel infectious diseases was arguably the most devastating consequence of European colonization” (Walker et al 2015).

Blanket Stories: Confluence, Heirloom, and Tenth Mountain Division, by Marie Watt, 2013, collection of Denver Art Museum, Denver, CO. Watt (Seneca) a textile artist whose Blanket Stories series presents piles of blankets, recalls at once the totem poles of Pacific Northwest cultures, and of the role that blankets that colonizers traded with Native Americans played in both the economy of exchange and the spread of disease, especially smallpox. Photograph: Denver Art Museum

For a brief definition of terms denoting conceptualized regions of the world related to this essay, click here.

A number of large factors contributed to the devastating impact of these diseases. The diseases Europeans brought with them were non-native diseases. With no natural resistance to the diseases that the explorers and colonists brought, illness spread rapidly among Indigenous peoples (see for example: Watts 1999, cook, 2004, Kelton 2007, Pringle 2015 and Goldberg 2017). Further, it was the spread of disease, combined with the perpetration of violence, and extraction of wealth and resources from Indigenous communities as carried out by explorers, colonizers, slavers and missionaries, that amplified Indigenous peoples vulnerability to the spread of disease (Alchon 2003, Malott et al 2009: 52; Heckenberger 2013: 63 and Rezéndez 2017: 17).

The Americas: 15th and 16th Centuries, after First Contact

Columbus, as he first arrives in India, is received by the inhabitants and honored with the bestowing of many gifts, by Theodor de Bry, 1594, from the series "India Occidentalis (Grand Voyages)” “America: Part Four.” Though, of course, it was the Americas and not India where Columbus first landed. Image: University of Houston Libraries

Europeans had contact with the Americas when on October 12, 1492, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus and a party of sailors, on an expedition sponsored by the Monarchy of Spain, contacted the Taino, Indigenous people of the Carribean, on the shores of San Salvador. Estimates of Taino population on the island of Hispaniola, where Columbus built his first town at the time of contact, vary, from 60,000 to 8 million. What is clear is that in 1548, 56 years after contact, only 500 Taino remained, their communities decimated by smallpox, influenza and other diseases and violent encounters with the Spanish.

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán (Hernán Cortés in front with a beard, Indigenous slaves at the rear), as depicted in the Codex Azcatitlan, 16th or 17th century. Image: Fordham University, azcatitlan23a.jpeg, Codex Aubin .

In 1519, Spanish soldiers, led by Hernán Cortés, moved from the Caribbean to the American mainland in search of more resources. Spanish Conquistador, Pánfilo de Narváez arrived at Cempoala, near what is today Veracruz, Mexico in April of 1520 with an expeditionary force. By August of that same year, smallpox was reported (McCaa 1994). Some months later, with the arrival of Cortés and his soldiers, the disease arrived in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, in September or October of 1520. The spread of disease among the Aztec is often credited to an infected Black slave, variably Francisco Eguía or Joan Garrido, though this is still debated, as some evidence indicates that infected Cuban Indians who were with Cortés brought the disease.

Figure of an Aztec Warrior, 14th century. The Mexica (Aztec) king Motecuhzoma greeted Cortés with various gifts, including gold figures such as this one, and Cortés sent them to Charles V, king of Spain and emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, who exhibited them in Brussels in 1520. Image: Cleveland Museum of Art

Whatever the particulars of its spread, it is certain that smallpox was the result of the arrival of the Spanish, and that half of the population of Tenochtilán died from the disease, including the Aztec ruler Cuitláhuac, successor to Moctezuma II who was ruler when Cortés arrived (ibid.). From Mexico, smallpox moved south. After:

“…exterminating most of the Aztecs. Subsequently it spread to Guatemala and the territories of Incas from 1525 to 1526. The disease rapidly exterminated a third to a half of the Araucanians in Haiti. Finally, the disease spread to Cuba and Peru, killing many Incas, including Huayna Capac, the King himself, and his successor, Huascar” (Sessa et al. 1999: 83).

Influenza, which would become a much bigger problem globally in the twentieth century, spread and became an epidemic in 1558 and 1559 in La Isabela, Dominican Republic, the first Spanish town in the Americas. And this was followed by an epidemic of measles in Mexico and Peru in 1530 – 1531 (ibid.).

What are the consequences for a people and culture, what does it mean to a society when half of your population dies in a matter of a few years? What does the loss of sacred knowledge, the death of skilled artisans, of food producers, of people who cared for children, mean for survivors? This was just the beginning of colonization in the Americas; the consequences were devastating, though not by any means total. In reading further, consider the resilience of those who did survive as you might consider also our current moment of a global pandemic.

The 17th Century

View of the village of Barcelos, formerly Aldeia de Mariuá. Scientific expedition of Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira, drawing by José Joaquim Freire, 1784. “In 1785-1786, during his journey to the Captaincy of São José do Rio Negro in order to assess the state of the commerce and economy, the Brazilian naturalist Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira collected valuable information about economic and natural resources, hygienic conditions of settlements, and diseases plaguing native populations. He mentioned, for example, the epidemic outbreaks of smallpox and measles that attacked Indians of the middle Rio Negro during the years 1763-1776 and also cited the devastating effects of the reconnaissance expedition of the upper Rio Negro region led by Colonel Lobo de Almada in 1784-1785 which gave rise to several epidemics of smallpox, measles, and fevers.” (Buchillet 2017: 109) Image: Collection of the Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil

Spain and Portugal continued to colonize in the Americas in the 17th century, mostly in the American Southwest and Central and South America. And with them, came epidemics, enslavement, exploitation, dislocation – and resistance.

“Over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the population of the state of Maranhão and Pará, a territory that roughly corresponds to modern Brazilian Amazonia, was struck by various epidemic outbreaks. From the mid-seventeenth to the mid- eighteenth century, there are records of serious epidemics in the 1660s, 1690s, 1720s and 1740s. Strongly dependent on indigenous labour (free and enslaved), the epidemics experienced by Colonial Amazonia disturbed the development of economic activities and influenced the forms in which compulsory labour was organized.” (Chambouleyron, et al. 2011: 1)

In 1758, for example:

“The administration of [Brazilian] colonial villages and towns was allocated to white military officers or to civilians (moradores) who received the title of “Director of Indians.” In these villages, Indians were compelled to work building community houses and homes for directors, in collective gardens of cotton, coffee, indigo etc., and gathering forest products. This new system of labour exploitation strongly deteriorated their way of life.” (Buchillet 2017: 109)

This deterioration of life included the cycling of epidemics and widespread illness and death, particularly from smallpox and measles, some of the years of major epidemic being: 1621, 1644, 1662, 1690, 1724, 1740, 1749, 1750-1758, 1762, 1763-1772, 1776, 1790, 1819, etc. (ibid.: 120). (for more on the Brazilian Amazon, see the Maxwell Museum online Exhibition: Heartbreak: A Love Letter to the Lost National Museum of Brazil, forthcoming).

Further North: Early European Encounters along the Atlantic

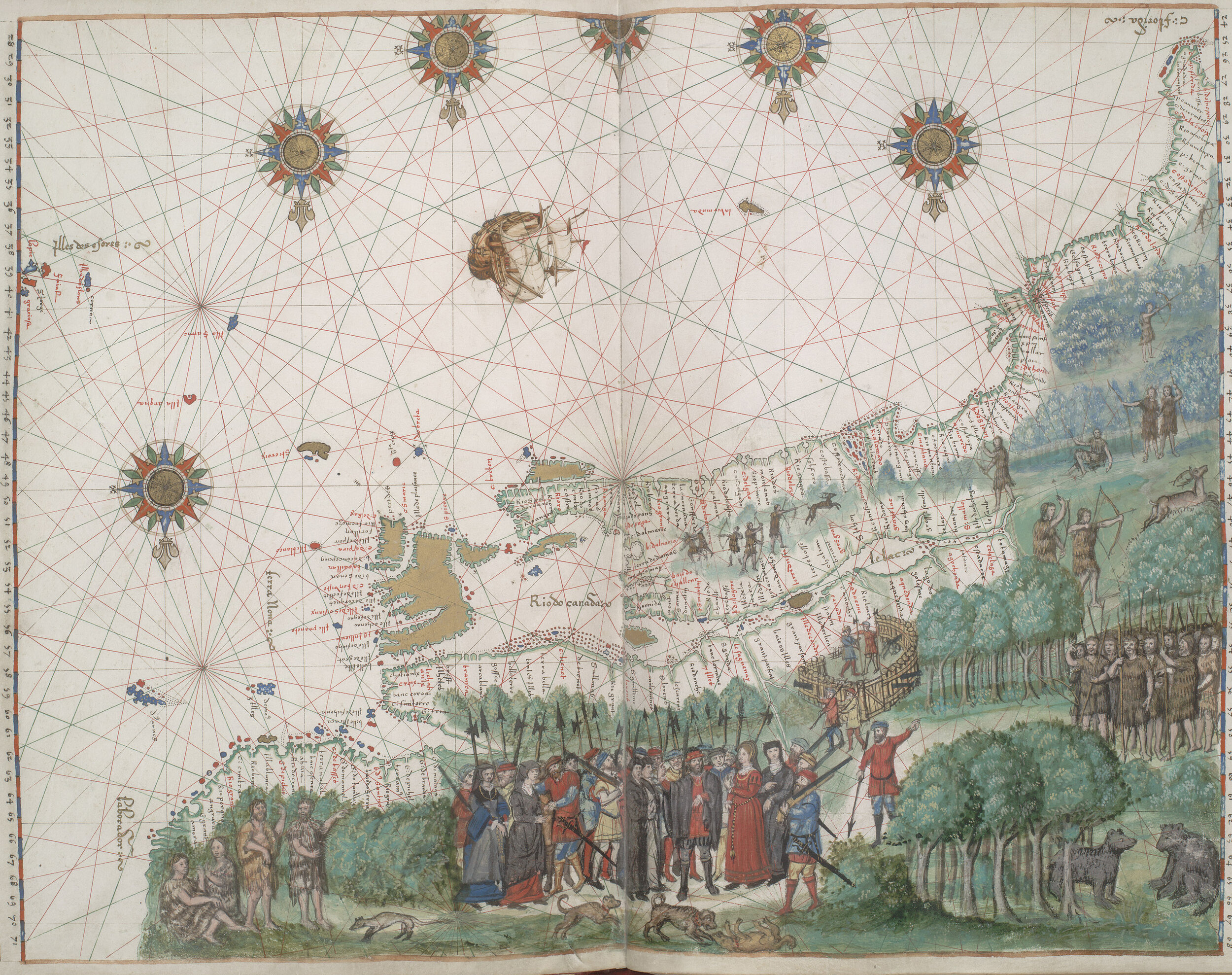

North America, east coast, in the Vallard Atlas, Nicholas Vallard de Dieppe, c. 1547, folio 9. An illustration of Europeans coming to North America, bringing pathogens and novel infections to Indigenous populations. Image: Huntington Library; photo UC Berkeley, Library, www.digital-scriptorium.org, CC BY-NC 4.0.

Meanwhile, further north, from as early as the 11th century, small groups of Europeans had found their way to North American shores, often undertaking exploratory expeditions inland, and here too, spreading disease as the went. For a list of some of the more major expeditions in the northern Atlantic, click here.

Portrait of an Indian Chief (possibly Wingina); with skin apron and on chest a copper gorget hung from neck, by John White, 1585-1593. Thomas Harriot, an official figure in Raleigh’s 1585 attempt to colonize Roanoke, Virginia, wrote of Chief Wingina falling ill: “Twice this Wiroans [chief] was so grievously sick that he was like to die, and as he lay languishing, doubting of any help by his own priests, and thinking he was in such danger for offending us and thereby our god, sent for some of us to pray and be a means to our God that it would please him either that he might live or after death dwell with him in bliss, so likewise were the requests of many others in the like case.” (Harriot 1590). Image: 1906,0509.1.21, The British Museum CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

However, it was not until the very late 16th and early 17th centuries that British and French colonists began to establish permanent settlements. Sir Walter Raleigh’s 1585 North American expedition landed in what is now Virginia, and Ralph Lane attempted to establish a colony at Roanoke. When that colony failed, another attempt was made in 1587 by John White. It became known in Britain as the “lost colony” due to the disappearance of the colony’s inhabitants. In 1604, Samuel de Champlain’s exploration of the northeastern seaboard of America, resulted in the founding of Acadia in 1610, in what is now eastern Quebec, the Maritime provinces and parts of Maine. In 1607, the first successful British settlement of Europeans was founded at Jamestown, Virginia. This was followed by the founding of Quebec in 1625.

The heightened spread of disease among Native Americans began as soon as Europeans launched their attempts to settle in North America. Thomas Harriot, an official figure in Lane’s 1585 attempt to colonize Roanoke, observed the spread of disease (likely influenza transmitted by the colonists) among the Indigenous people they came into contact with (Mires 1994: 30):

“Within a few days after our departure from every such [Indian] town, the people began to die very fast, and many in short space; in some towns about twenty, in some forty, in some sixty, & in one six score [6 x 20 = 120], which in truth was very many in respect of their numbers. . . . The disease was also so strange that they neither knew what it was nor how to cure it.” (Harriot 1590)

Dried eel skin used for healing, mid-20th century. Made by Turkey Tayac (Phillip Sheridan Proctor), member of the Piscataway Indian Nation located in Maryland. By the early seventeenth century, the Piscataway had come to generally control the other Algonquian-speaking Native American groups on the north bank of the Potomac River. By the end of the 17th century, the Piscataway, like many groups in the region, having been ravaged by disease and violence, migrated west. Turkey Tayac, the maker of this tanned eel skin, played a large role in reviving American Indian cultures in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeast. Image: Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of the American Indian

Slightly further north, “The cumulative effects of war, disease, and subjugation decimated the Native Americans of the upper Potomac. Thousands lived in the river valley in 1608, but by 1708, just a few hundred remained – beaten, scattered, and subject to the Crown” (Asch and Musgrove 2019: 14).

Philip, King of Mount Hope, from Benjamin Church’s The Entertaining History of King Philip’s War, line engraving, colored by hand, by the American engraver and silversmith Paul Revere, 1772. Pictured is Metacomet, the sachem (chief) of the Wampanoags, who took the name “King Philip” as a reflection of the friendliness between the Mayflower pilgrims, and his father, Massasoit. “King Philips War” (1675 – 1678) was an armed conflict between Native Americans of New England, and colonists and the Native Americans who allied themselves with them. Image: Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery. Yale University.

Further north still, in 1616, on the coast of Massachusetts, a plague swept in. Chroniclers observed that with so many Native inhabitants dying that all could not be buried, and many were left lying in heaps. Thomas Morton, an English colonist, described the site as “a new found Golgotha” (meaning a place littered with bones, in reference to the hill of Calvary where Christ was crucified [Seeman 2011: 145]). The plague cleared Boston Harbor of its Indigenous inhabitants, killing 90 percent of the 4,500 Native occupants of the area (Landrigan 2020).

Wampanoag wooden ladle, collected in 1681 by Samuel Thrasher, who was born in 1640, the year after the town of Tauton, Massachusetts was settled by English colonists. At the time he came into possession of this ladle, he was a highway surveyor, and would likely have been part of the English forces during King Philips War. It is unclear how he came to own this Wampanoag ladle, during a time when the Wampanoag population was decimated by disease, war and being sold into the slave trade. On a contemporary note, on March 30, 2020, while the Covid-19 pandemic was taking hold in the United States, the Trump administration rescinded the reservation status for more than 300 acres of land in Massachusetts for the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe (Kelley 2020). Image: Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian.

Among those who were wiped out were the Wampanoag who lived along the coast from Plymouth to Boston. Wampanoag who lived south of Plymouth were spared by this round, including their leader Metacomet, who, along with other survivors, resisted the colonists land grab through an armed resistance that came to be known as “King Philips War” (1675 – 1678), “But disease persisted among the tribe, weakening it further. By the war’s outbreak, the Wampanoag Indian population fell to 2,500 from as many as 5,500. Those who weren’t killed in the war were sold into slavery, moved to praying towns or migrated west. King Philip’s War [and the spread of disease] virtually obliterated the Wampanoag” (ibid).

Narragansett basket, 1675. This basket is one of only two known surviving 17th century Algonkian baskets. Made at a time when the Narragansett were at the tail end of a dramatic decrease in population due to disease and violent conflict with colonists, and many of the defeated Native Americans were sold into slavery in the West Indies at the end of King Philips War (Slotkin and Folsom 2011: 34 – 52). Image: The Rhode Island Historical Society

In 1633 another epidemic, likely smallpox, swept all of New England, New York and Quebec. The epidemic did not much affect the colonists, but greatly impacted the Indigenous people of the region “The epidemic, apparently the northeast Algonquin’s first experience with smallpox, became the greatest epidemic ever to strike the New England Indians. Overall mortality approached 86 percent” (Jones 2004: 31). Many tribes were affected, including the Narragansett, at the time the largest tribe of New England. “The Narragansetts’ first epidemic was smallpox in 1633, which killed 700 of them. Chronic ailments further reduced their numbers to 5,000 by the outbreak of King Philip’s War. Wrote Roger Williams in 1643… After King Philip’s War fewer than 500 Narragansetts remained.” (Landrigan 2020).

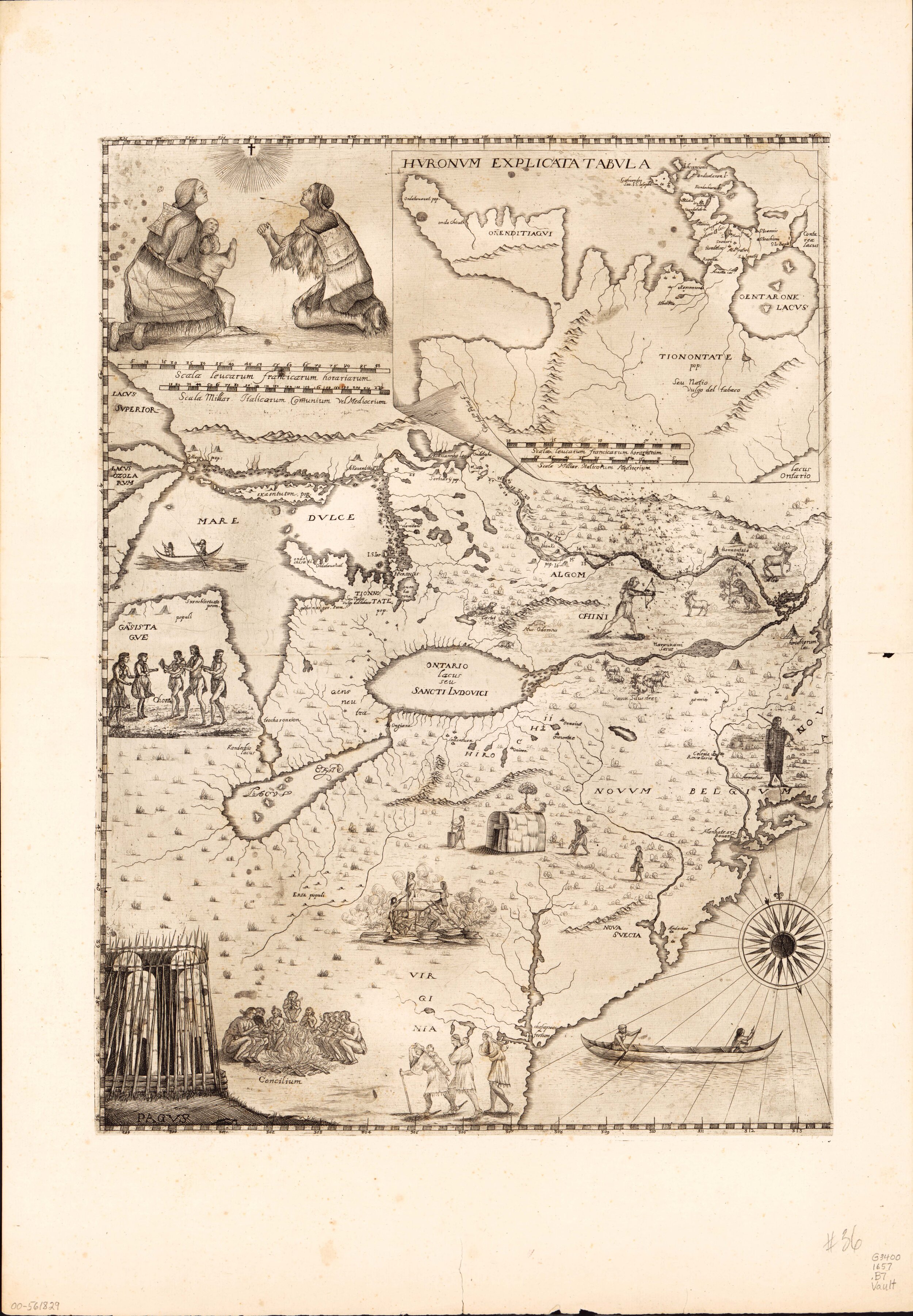

Novae Franciae accurata delineation (Accurate delineation of New France), by Francesco Giuseppe Bressani, 1657, Macerata, Italy (?). “Map of North America, from Newfoundland to Lake Superior, and from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Chesapeake Bay. A small map of Huronia …. Engraving representing a family of Native Americans in prayer in the upper left corner of the western leaf. Several scenes representing Native Americans in various types of activities.” Image: Library and Archives Canada, Virtualmuseum.ca

Moving further north still, with the founding of Acadia and the subsequent founding of Quebec, Jesuits recorded that by 1637 – 27 years after the arrival of the French in Acadia and 12 years after the founding of Quebec – 50 percent of the Huron had died from fevers and smallpox (Jones 2004: 42). The Huron asked of the Jesuit priests “… why [had] so many of them died, saying that since the coming of the French their nation was going to destruction,—that before they had seen Europeans only the old people died, but that now more young than old died.” (Jeune 1898, 11: 193).

(Detail) Iroquois war club from King Phillip’s War, ca 1675-76. The war, also known as The First Indian War, was a conflict between English colonists and numerous Native tribes, and its dates were situated between two major epidemics for the Iroquois. Regarding the club, upon attaining adulthood, Iroquois men found his guardian spirit, or manitou, a lifelong protector. His manitou was in turn tattooed on his skin, typically his face, which was sometimes, as seen here, further engraved on his war club. The owner of the club may have been Seneca or Mohawk, based on the style of tattooing (see: Krutak 2013). Image: 795/826, Fenimore Art Museum, New York State Historical Association.

Beginning in the 1630s, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (called the Iroquois by the French, consisting of the nations of the Mohawks, Onondagas, Oneidas, Senecas, and Cayugas,) suffered waves of disease epidemics brought by Europeans. These continued on and took place “…in 1647, 1656, 1661, 1668, 1673, and 1676, so that by the end of the seventeenth century, they had suffered an estimated 95 percent population loss” (Ethridge 2013: 94). By the close of the 17th century, the Indigenous occupants of New England and the Canadian Maritimes were devastatingly reduced (Jones 2004: 32), as English and French colonists moved further south and west and inland.

North American West Coast: Early Encounters

Chumash carved whale, 16th or 17th century. The Chumash were prolific carvers of stone effigy figures, such as this whale, with representations of marine animals and water birds being most commonly represented (Hoover 1974: 34). At the time this whale was carved (1519 - 1769), the Chumash would have already begun having contact with Europeans. During many early European expeditions to the west coast of America, it is possible that the limited contact expeditions had with Indigenous inhabitants, particularly the Chumash, likely resulted in the spread of disease, though certainly, beginning in the 18th century, the founding of missions in the area that is now California, had devastating effects on the California Indians. Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

On the west coast, the reduction of the Indigenous populations of California through the spread of disease is often attributed to the beginning of Franciscan missionization in 1769, (the Mission of San Diego). In fact, Afro-Eurasian diseases likely began spreading in the mid-16th century, the result of early Spanish maritime voyages some two centuries before the arrival of Spanish colonists, particularly amongst the Chumash (Reff 1991, and Preston 1996: 2 – 3).

The 18th through 19th Centuries

Seven Cherokees standing in a woodland setting; they wear European dress with moccasins; they are bare-headed (apart from the king, OK Oukah Ulah who has a feather head-dress) and tattoos on their heads are visible; they carry such objects as a bow, an axe and a gourd rattle, as well as a rifle and swords. By Isaac Basire after Markhem, 1730. By the time of this engraving, the spread of disease had begun devastating the Cherokee. Image: Y,1.110, The British Museum CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

With the establishment of the United States after the American Revolution, the 18th and 19th century saw epidemics of cholera and yellow fever (ibid.). The spread of syphilis had enormous tolls on Native communities through the machinations of colonization – specifically through sexual violence perpetrated against Indigenous women - from the time of contact until 1943, when penicillin was introduced (Sessa et al 1999: 84; Frith 2012, Gupta 2017: 1). The origins of the disease have yet to be decisively determined, originating either in Afro-Eurasia or the Americas (Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History 2018 and Hemarajata 2019).

In North America, smallpox in particular travelled, moving south, reaching the Creek and Cherokee in the 1730s (Kelton 2016), and moving west with the establishment of forts and trading posts, with outbreaks in 1702, 1736 and 1738 in the area that is now Canada, and reaching the Canadian western Plains by 1780, with outbreaks on the Saskatchewan River (Houston and Houston 2000).

An East View of the Great Cataract of Niagara, by Captain Thomas Davies, 1762. Two Iroquois men stand in the foreground. This First Nation tribe sided with the British against the French during the war. The Iroquois had already been suffering from waves of disease for more than one hundred years when this illustration was made. Many of the members of tribes from further west who came to fight in this war, went home sick and carried disease back west with them. Image: The National Army Museum, UK.

In 1756 smallpox reached the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes, brought by returning Native fighters who had contracted the disease in the east when they were recruited by the French to fight in the Seven Years’ War against the British (Ostler 2020).

(Detail) Pipe tomahawk presented to Chief Tecumseh (Shawnee, 1768–1813), ca. 1812, Ohio. This pipe was a gift to the Shawnee war chief Tecumseh in 1812, given to him at Fort Malden by Colonel Henry Procter, during the War of 1812. Just a few years previous, Indians from many nations of the region, including Shawnee, had died in an epidemic 1808 – 1809 in Prophetstown, Indiana (a town founded by Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa) near Fort Malden (Cave 2002: 646). Image: Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of the American Indian.

Smallpox reached the Plains in the United States by the early and mid 1700s, with outbreaks among the Kansa, Arikara, Lower Loup and Pawnee, spiking in 1780 with the beginning of the “Fur Trade Wars” (Daschuk 2019: xvii and 22). Although a vaccination for smallpox was discovered in 1796, dispersal was limited, particularly among Indigenous nations on the Plains throughout the 19th century, culminating in a devastating outbreak in 1837, which greatly affected the Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Assiniboine, Cree and Nitsitapi, who had not been vaccinated against the disease, while many bands of the Sioux, who had been vaccinated, did not suffer to the same degree (ibid..: 67 - 70).

Beaded moccasins, Apsáalooke (Crow), late 19th century, courtesy The Saint Louis Art Museum (15:1934a,b). These moccasins were made by a Crow woman whose name is unknown to us, was made during the time of the last and worst outbreak of smallpox in that region of the Plains. Even though a smallpox vaccine had been available for almost a century, it was not distributed to all Native Americans in the region. Image: Saint Louis Art Museum

An outbreak of smallpox on the Northern Plains in 1869-1870 was, the last of the pre-treaty era (Binnema 2006: 128). Many Nations and tribes were affected, including the Blackfoot, Cree and Assiniboine (Hackett 2004: 609; Binnema 2006: 125 - 128). At least a third of the First Nations and Métis populations died. “The coincidence of the outbreak with a political crisis in Red River [a region of Manitoba, CA abutting Hudson Bay] undermined the HBC’s [Hudson’s Bay Company] ability to counter the spread of the disease. The chief officer in the infected country, W.J. Christie, requested the immediate delivery of vaccine in August of 1869. None came until April 1870” (ibid..: 84).

Men’s abalone earrings, Hupa, late 18th early 19th century. “The Hupa and Yurok peoples have lived along the Klamath River [northern California] for thousands of years, sustained by the bounty of the waters and trade with one another and other tribes.” The Hupa, like all California Indians, were hit hard by epidemics, and by 1864, when they moved onto a reservation on their ancestral lands, their numbers fell to 650, having been perhaps two or even three times that many pre-contact. Image: Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History.

With the beginning of the mission period on the west coast (1769 - 1833), smallpox broke out in 1769 at the San Diego Mission, and in 1781 in Baja. Other infectious diseases, including measles and syphilis plagued the California Indians and other Indigenous groups up and down the coast (Dowd 2017). By 1848, the population of California Indians was reduced by 90 percent, in large part due to disease (Nabakov 2007).

Woven basket, Unknown Clatsop artist, ca. early 18th century. The Reverend J. L. Parish, a missionary and early trustee of Willamette University, was given this basket in the early 1840s by the Clatsop Indians on the Oregon coast, according to his descendants. Of his time as a traveling minister on the so-called Yamhill circuit, Reverend Parish had this to say “The year that my party arrived I presume there were 500 Indians that died in this valley with chills and fever and typhoid fever. They were first attacked with chills, and then ran into a lower typhoid” (Parrish 2017). Image: Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Willamette University.

Disease, particularly smallpox, moved up the west coast, reaching Oregon around 1781, affecting the Clatsop and Chinook (Boyd 2019). Traveling further north still, the Indigenous nations of the Northwest coast were also impacted, though there is little documentation of those epidemics. However, it was an epidemic of the disease in 1862 that devastated the Northwest coast and Puget Sound Indigenous Nations (Boyd 1999: 173).

Chief’s headdress with carved frontlet, Haida, ca. 1881. The frontlet is a portrait of Suudaahl (also ‘Josephine Gladstone’), just twelve years old at the time it was carved. She was the daughter of Chief Daniel Elljuuwas, who may have also carved the frontlet, of the community of Skidegate, Haida Gwaii. Suudaahl was born in 1869 in Tanu, seven years after the deadly smallpox outbreak. Image: Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History.

In the late 18th century, Euro-Americans began regular contact with the Northwest Coast. There they encountered a reported population conservatively estimated at over 180,000, among them the Tlingit, Haida, Kwakwaka'wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, Coast Salish, and Chinookans. A century later, only about 35,000 were left (Ibid.: 3). The steamship The Brother Jonathan arrived in Victoria on April 12th of 1862. With it came smallpox. The disease began to spread, particularly decimating the Haida, and affecting the Tsimshian, Kwakwaka'wakw, Stikine Tlingit (mainland Tlingit), and Heiltsuk, who were located in a trading camp outside of Victoria. When their illnesses were reported, they were forced to leave Victoria and return to their home villages, bringing the disease with them (ibid..: 176).

Naxnox mask, Tsimshian, Nisga’a or Gitxsan, 19th century. Carved alder bird mask, depicting Smallpox: “Naxnox is a personification of power, or that which is manifest in halait [Shamanic or ritual manifestation of power]” (Halpin 1993: 282), and such masks were named. “The entire naxnox naming system was a metaphorical elaboration on the theme of death. The various physical infirmities represented by naxnox names – old age, lameness, deafness, smallpox, etc. – were metaphors of physical death” (Miller 2000: 92). Image: Museum of Vancouver

The Tsimshian had already lost about one third of their population to an 1836 smallpox epidemic when the epidemic of 1862 spread to them. It also reached many other Northwest coast groups, including the Nisga’a and Gitxsan, who may have been spared the 1836 epidemic, but suffered unimaginably in the later epidemic (Boyd and Boyd 1999: 175, 216).

Measles, by Ruth Cuthand, 2009. “From her series Trading, Saskatchewan-based artist Ruth Cuthand creates a visual metaphor that outlines how early settler/Native relationships influenced First Nation people’s living conditions and wellbeing in Canada.” Ruth Cuthand is an artist of Plains Cree, Scottish and Irish ancestry Image: Ruthcuthand.ca

Smallpox was one of the most devastating of the introduced diseases for Native peoples in the Americas. Outbreaks of other diseases—influenza, measles, typhus, pneumonia, scarlet fever, malaria, and yellow fever, among others likewise proved dire. (Maslin and Lewis 2018).

The Belle of the Navajos, Plate 54, possibly by the Duhem Bros., ca. September 1866, en route to, or at Fort Sumner, New Mexico Territory. From a collection of photographs, “Souvenir of New Mexico” depicting the first known photographs of Navajo, during their internment in Hweéldi, or the Place of suffering, where they suffered from pneumonia, dysentery, and particularly smallpox, as well as malnutrition and violence. Image: Palace of the Governors Photo Archives, New Mexico History Museum.

It was not just a lack of exposure to these novel infections that made colonized Indigenous peoples of the Americas (and elsewhere) vulnerable to disease, but it was colonization itself that invited the spread of sickness among original inhabitants. For example, in the American Southwest, disease and illness that might have otherwise been avoided among the Navajo were contracted when they were taken from their lands beginning in 1864 and imprisoned at the Bosque Redondo for four years (see subchapters The Rio Grande Drainage and The Virgin of Guadalupe in this chapter on Colonization).

Phase III Chief’s Style Blanket, Navajo, 1860 – 1880. The Navajo weaving tradition is centuries old. The arrival of the Spanish and their sheep in the 1600s saw the foundation of the weaving tradition that we know today. Collecting of Navajo weavings began roughly a little more than 150 years ago, when Anglo-Americans began settling in greater numbers in the Southwest after the Mexican American War of 1848. Military officers, territory governors, government survey party members and Indian agents became collectors of Navajo weavings (Webster 2017:56-57). Navajo women continued to weave during the Navajo internment at the Bosque Redondo, weaving blankets such as the one seen here, woven during perhaps the most difficult period of Navajo history, fraught with violence, disease and huge loss of life, “And soon after the Diné’s release from Bosque Redondo and return to Navajo land in 1868, anthropologists such as the Bureau of American Ethnology’s John Wesley Powell began making their first scientific museum collections of Navajo and other southwestern textiles” (ibid. 57) .Image: 63.34.128, Maxwell Museum of Anthropology.

For the next four years, in a plan devised by U.S. Army Brigadier General James H. Carleton, the Navajo were forcibly removed from their homelands. Made to walk hundreds of miles in all weather conditions, on a journey referred to as the Long Walk, they were interred in a spot in southern New Mexico called the Bosque Redondo at Fort Sumner. The Navajo call it Hweéldi, or the Place of Suffering (Romanek 2019). “Survivors of the Long Walk arrived at a place with poor soil, alkaline water, and sparse trees” (Ibid..: 56), where they spent the next four years starving and dying of disease, “So many Diné [Navajo] died at Hweéldi—over two thousand—that for decades they refused to speak of their experience” (Denetdale 2019: xiii), dying of pneumonia, dysentery, and particularly smallpox, “Hundreds died en route, and hundreds if not thousands more Navajos died from smallpox in the first year of imprisonment” (Romanek 2019: 53). Additionally, syphilis was rampant at the Bosque Redondo, as Navajo “…women were reduced to selling sex for a handful of cornmeal” (Denetdale 2019: xii). It was colonization and the removal of the Navajo from their homeland, and their forced placement on insufficient land with insufficient supplies, that brought disease and death to the Navajo in the mid-19th century to such a great extent.

The Trajectory of the Spread of Disease with European Contact in Other Parts of the World

Colonizing Europeans brought new diseases to the Americas as well as to Australia and the Pacific Islands. The consequences were shockingly devastating in the sheer volume of the loss of life and decimation of Indigenous populations. Young and old were equally affected. Knowledge keepers, food producers, skilled artisans, leaders, and countless others were lost as diseases spread indiscriminately through communities. Those who survived faced the ongoing depredations of colonialism as they strove to maintain, restore, and transform their ways of being.

Carved shield, Aboriginal Australian, ca. late 18th century. Possibly collected on Captain Cook’s first voyage to the Pacific, when he visited Botany Bay near present day Sydney, New South Wales, in 1770, though recent scholarship also argues that this is not the shield described in the first encounter of the British with Aboriginal Australians. As Joseph Banks, botanist on the voyage, described: “Defensive weapons we saw only in Sting-Rays [Botany] bay and there only a single instance—a man who attempted to oppose our Landing came down to the Beach with a shield of an oblong shape about 3 feet long and 11/2 broad made of the bark of a tree; this he left behind when he ran away and we found upon taking it up that it plainly had been pierced through with a single pointed lance near the centre” (Beaglehole and Bans 1962: 133). In just over a year from the time of that first contact, at least half of the inhabitants of the Sydney region were dead, of smallpox. Image: Oc1978,Q.839, The British Museum CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Aboriginal Australians roughly numbered 750,000 and had inhabited their continent for approximately 75,000 years when Captain James Cook landed at Botany Bay near present day Sydney, New South Wales, during his first Pacific voyage in 1770 (Michel 2018: 55). In just over a year from that first contact, at least half of the inhabitants of the Sydney region were dead of smallpox. Governor Arthur Phillip, first Governor of New South Wales, wrote to British politician Lord Sydney, “It is not possible to determine the number of natives who were carried off by this fatal disorder. It must be great; and judging from the information from the native now living with us, who had recovered from the disorder before he was taken, one half of those who inhabit this part of the country died” (Bladen and Britton 1893: 308). Later, measles, influenza and syphilis would also devastate Aboriginal communities.

Ring or earring ornamented with European shirt buttons, ca. late 19th century, Fergusson Island, Papua New Guinea. This is from one of the oldest and largest collections of Pacific Islands objects in a museum, collected by P. G. T. Black, a British Agent, who began collecting in the 1880s. Europeans – the Spanish and the Portuguese - began making contact in the Pacific Islands beginning in the 16th century, but it was really only with sustained contact in the 18th century that “…Infectious diseases depopulated many isolated Pacific islands when they were first exposed to global pathogen circulation…” with dysentery being a leading cause (Shanks 2016: 273). Image: C10476, Buffalo Museum of Science.

Once sustained contact and colonization from Europeans began in the Pacific Islands, great de-population from infectious diseases soon followed. Indigenous inhabitants were exposed to the pathogens that outsiders brought (Shanks 2016: 71). This happened much later than in much of the Americas, with diseases taking hold in the 18th century and epidemics beginning in the 19th.

Necklace of eight whale ivory figures suspended from plaited coir cord, 1875-80, Fiji. Ivory, pearl and turtleshell necklaces were part of a system of gift exchange between Fijian chiefs and the first British Governor of the island, Arthur Hamilton-Gordon. This necklace was probably gifted to his wife, Lady Gordon in or around the same year that an epidemic of measles swept Fiji, the disease having been brought there by the Australian naval ship, the HMS Dido (Shanks 2016: 76). Image: Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology , CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Two Islands, Fiji in 1875 and Samoa in 1918, were particularly hard hit. Both were further destabilized through the loss of key leaders during epidemics (ibid.).

Slavery

A guaiacum officinale, plant specimen, from the Sloane Herbarium, collected during Hans Sloane's voyage to Jamaica in 1687. In the 16th century, Europeans proposed Guaiacum, also referred to as ‘lignum sanctum’ or ‘holy wood’ (Munger 1949:200), as a cure for syphilis. It was not a particularly effective treatment, but one of the theories around it was that God had provided a cure in the same place as the origin of syphilis, namely Hispanolia, as it was thought at the time that is where the disease originated (the site of original European contact with the Americas), though its origin is still debated: “a scant sixteen years after the Columbian landfall, guaiacum (guaiacum officinale) was being imported in large quantities from the Caribbean to Europe to treat the French disease (syphilis)” (Voeks and Green 2018: 546). Sir Hans Sloane was founder of the British Museum, and he collected, among other things, objects of the slave trade and botanical samples in the West Indies, where his wife had a slave plantation, and where he derived his wealth (Sheller 2008: 20). Those samples reside in the Sir Hans Sloan Herbarium and collection at the Museum of Natural History, London. Image: The Natural History Museum, London . Charlie Jarvis (2016). Dataset: Sloane Herbarium. Resource: Sloane Herbarium. Natural History Museum Data Portal (data.nhm.ac.uk).https://doi.org/10.5519/0081520.

Long before the so-called “European Age of Exploration,” ships plied the waters linking Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Europeans were latecomers to the extensive centuries-old maritime networks that spread goods, technologies, knowledge, beliefs – and, diseases. European maritime exploration began nearly a century before the Spanish reached the Americas with the Spanish invasion of the Canary Islands in 1402 and Portuguese exploration of the North African coast in 1415. Many of these parts of the world already had experiences with and immunity to many of the diseases the Europeans brought. For example, recent archeological research indicates that the plague may have been brought to West Africa in the early 15th century CE, pre-colonization, by merchant and travelers along Trans-Saharan trade routes (Gallagher and Dueppen 2018). In fact, Europeans were sometimes at great risk for the diseases native to the foreign lands they were encountering (Russell-Wood 1998: 109, 180). Syphilis was the exception and was transmitted with devastating consequences wherever colonizers went (ibid. 120).

(Detail) diagram of Brookes slave ship from the Atlantic slave trade, 1787, from “The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade by the British Parliament,” published 1808 (522.f.23). Built in Liverpool in the 1780s and named after its owner and builder, James Brookes. On three voyages between 1781 and 1785 the ship carried over 600 enslaved Africans on the middle passage from West Africa to the Caribbean; many died [from illness and disease] as a result of the terrible conditions on board” (Brookes Slave Ship). Image: British Library.

Even among populations with resistance to diseases, the larger functioning and apparatus of the institutions of empire building and colonization brought an overwhelming burden of sickness and disease to Indigenous populations the world over. Enslavement, forced relocations, disruption of subsistence economies, and, in some regions, the process of urbanization in previously rural areas under colonial rulers, increased the vulnerability of subjugated communities to disease and facilitated their rapid spread (Unite for Sight 2000). In this manner, colonization and the attending pathogens of disease spread to other areas of European conquest beginning in the 15th century, as Europeans encountered and later colonized parts of Oceania, Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

Pipe in the shape of a rifle, Chockwe people, 19th or 20th century, Angola. “The Chokwe peoples occupy the broad expanse of open savanna in present-day Angola and Democratic Republic of Congo. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Chokwe chiefs became increasingly involved in trade with Europeans who sought rubber, wax, and ivory as well as African slaves for their colonies in the New World. Slaves were often exchanged for firearms, and these were employed in raids on neighboring peoples that produced more captives to sell to European traders. Local leaders who prospered from this exchange frequently commissioned prestige items from local artisans to indicate their wealth and power. This tobacco pipe is one such item that demonstrates the degree to which warfare, the slave trade, and elite arts were intertwined at this time. The pipe itself was the prerogative of individuals who could afford expensive imported tobacco, generally by trading slaves, while the rifle refers to the means by which such slaves were acquired” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Image: 1977.462.1, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Africa was the last large region colonized by Europeans (1880 – 1910) (Tilley 2016: 743), though direct European contact with Africa began in the 1400s in West Africa, when Europeans also commenced the slave trade. European enslavement and transport of captured Africans to plantations in the Americas would expand dramatically over succeeding centuries, with 10-15 million people taken from their homes from the 16th- 19th centuries. Many did not survive the Middle Passage:

“The prime cause of death was gastrointestinal complaints, caused by dirty, unhygienic conditions. Flux, dysentery and severe diarrhea were the chief symptoms. Dr. Alexander Falconbridge, who had been a surgeon on English slave vessels, noted that some ships’ holds were ‘so covered with blood and mucus in consequence of the flux, that it resembled a slaughter house.’ But there were also deaths from dropsy, scarlet and yellow fever, malignant fever, tuberculosis and a host of other diseases. The incidence of disease followed the normal pattern of epidemics’ deaths reached a peak during the first third of the Middle Passage, before falling and leveling off later in the voyage. However, dehydration and starvation then sometimes occurred as supplies of food and water ran out.” (Anderson 2011)

Ironically, it was the spread of disease itself that was one of the driving factors in slavery. With so many Indigenous Americans dying from disease, European colonizers could not enslave them in the numbers they had intended. And European laborers were themselves vulnerable to diseases in the tropical climate of the Caribbean and were not considered a reliable source of labor. The enslavement of Africans was a solution to these problems (Thornton 2017: 142). And so it was that African slaves were exposed to and suffered new and old diseases both in their passage from Africa to the Americas and in the Americas. They were simultaneously carriers of diseases that would go on to infect Indigenous Americans and Europeans settlers and colonists upon their arrival in the Americas.

Apentema (aka Apentemma) drum, the Akan people, ca. late 17th or early 18th century, Ghana, West Africa. The drum comes from the Akan people, a group which includes the Asante and Fante kingdoms and it would have been a high-status object, possibly used at court and probably part of a whole drum orchestra. The drum was collected in the colony of Virginia in the early 17th century, entering the collection of the British Museum in 1735, making this possibly the oldest known object of the transatlantic slave trade existing in a museum collection from the Americas. It is most likely that the drum was taken on a slave ship – but not by a slave, because slaves brought nothing with them. Drums like this were used for what was rather called ‘dancing the slaves’, whereby, to maintain the health of the slaves and prevent the spread of illness, for the purpose of maximum profits, slaves were brought up on deck and forced to dance to the beat of drums in the fresh air. Image: AMSLMisc.1368, The British Museum CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

For example, the first permanent English settlement in North America, was Jamestown, Virginia, founded in 1607. The first African slaves in America arrived in Jamestown in 1619. Dutch and English privateers, who were carrying slaves as cargo (slaves that they had stolen from a Portuguese slave ship that had been bound for Vera Cruz) traded the Africans for food with the colonists (Walsh 2012: 113). The colonists who settled in Jamestown themselves suffered greatly from disease, mainly related to the encounter with a new environment (Blanton 2000 and Walsh 2012: 92), and so too did the first captive Africans the colonists brought with them. These first African slaves on the North American continent arrived from the Kingdom of Ndongo in Angola, west central Africa, having been captured during war with the Portuguese. Just like the colonists, the slaves suffered new diseases in a new environment, typhoid and dysentery most prominent among them (Blanton 2000: 78, and Earle 1979: 365).

Lancet, 1720-1800, owned by Edward Jenner, England. A lancet like this would have been used by John Quier and James Thomson to carry out their smallpox experiments on slaves (Shiebinger 2017: 93). Quier and Thomson purposely infected slaves with smallpox, in 1768 and 1810 respectively, in their search for a cure to smallpox (ibid.: 92). Image: Wellcome Library

It was also the case that slaves were used to experiment on medically, particularly in the search for a cure for diseases that Europeans suffered from, diseases such as smallpox, malaria and yellow fever. Finding remedies became an important business. In the 18th and 19th centuries John Quier (experimenting in 1768), a British doctor and slave-owner in Jamaica, and James Thomson, a British doctor in Jamaica (experimenting in 1810) carried out experiments on slaves in search of a cure for smallpox. Together, they experimented on upward of 850 slaves, making four or five small punctures in the arms or legs of slave subjects for the purpose of inoculation with a lancet, thereby infecting their subjects (Shiebinger 2017: 93).

(Detail) embroidered coverlet in the Indo-Portuguese quilting tradition, first quarter of the 17th century, Satgaon, Bengal. This quilt was made at a time when the Portuguese had been trading in India for more than 100 years, bringing trade goods and syphilis with them. Image: T.438-1882, The Victoria and Albert Museum.

In British colonies, only Calcutta and West African slave ports reached the levels of mortality from disease of early colonial Virginia (Earle 1992: 57). In the 15th century, the Portuguese were some of the earliest and busiest explorers and colonizers, building the Elmina Castle in Ghana in 1482, which was their first trading post in that country, a holding and shipping port for slaves bound for the Americas. This particular device of colonization, the enslavement of people, like the example of the internment of the Navajo above, gave rise to the spread of disease not necessarily as a particular lack of immunity to a novel illness. Rather, the entire process of enslavement, from capture to the middle passage to working the fields and plantations of the Americas, was a set-up for the spread of disease. And so, for instance, Elmina castle, where “Up to 1,000 captives could be crammed in these dark, airless, sweltering-hot cells even though they were designed to hold only one-fifth of that number. Consequently, yellow fever, infections and communicable diseases were rampant” (Adjaye 2018: 14-15).

Syphilis

As Europeans continued to increasingly explore, colonize and enslave, disease and ill health continued to be visited upon original inhabitants and Indigenous peoples.

And syphilis was wreaking havoc:

“Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease caused by Treponema Pallidum, a bacterium classified under Spirochaets phylum, Spirochaetales order, Spirochaetaceae family, but there are at least three more known species causing human treponemal diseases such as Treponema pertenue that causes yaws, Treponema carateum causing pinta and Treponema pallidum endemicum-responsible for bejel or endemic syphilis.” (Tampa et al 2014)

The origins of syphilis is still subject to debate, with three theories as to its origins: the pre-Colombian hypothesis, whereby the claim is that “not only syphilis was widely spread in both Old and New World, but also the other treponemal diseases”; the unitarian hypothesis, which is “a variant of the pre-Columbian hypothesis, it advocates that the treponemal diseases had always had a global distribution…[and], both syphilis and non-venereal treponemal diseases are variants of the same infections and the clinical differences happen only because of geographic and climate variations and to the degree of cultural development of populations within disparate areas”; and lastly, the Colombian hypothesis, whereby the claim is that “…the navigators in Columbus fleet would have brought the affliction on their return form the New World in 1493” (ibid.). Recent decoding of first ancient syphilis genomes indicates a complicated story that gives greater credence to the first two theories, but the origins of syphilis remains a question (Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History 2018 and Hemarajata 2019).

Because of the stigma associated with this and other sexually transmitted diseases, the debate regarding the origins of syphilis carries cultural and political implications, as well as scientific:

“From the very beginning, syphilis has been a stigmatized, disgraceful disease; each country whose population was affected by the infection blamed the neighboring (and sometimes enemy) countries for the outbreak. So, the inhabitants of today’s Italy, Germany and United Kingdom named syphilis ‘the French disease’, the French named it ‘the Neapolitan disease’, the Russians assigned the name of ‘Polish disease’, the Polish called it ‘the German disease’, The Danish, the Portuguese and the inhabitants of Northern Africa named it ‘the Spanish/Castilian disease’ and the Turks coined the term ‘Christian disease’. Moreover, in Northern India, the Muslims blamed the Hindu for the outbreak of the affliction. However, the Hindu blamed the Muslims and in the end everyone blamed the Europeans.” (Tampa et al 2014)

Artificial nose made of plated metal, ca. 17th or 18th century, Europe. Such noses would have been made to replace an original, which may have been congenitally absent or deformed, lost through accident or during combat or due to a degenerative disease, such as syphilis. Image: A641037, Science Museum , London.

What is clear is that once colonizing Europeans had syphilis, they spread it wherever they travelled. The first recorded case of syphilis was in 1495, two years after Columbus and his crew had return to Spain from their initial voyage. The outbreak happened in Italy, when the French king Charles the VIII invaded Naples (Quetel 2004: 10). “Most of King Charles’s troops were mercenaries, not only from France but also from Flanders, Switzerland, Germany, Italy and Spain” (Evans 2013). The root of the word “syphilis” comes from the Latin epic poem Syphilis sive morbus gallicus – ‘Syphilis or The French Disease’, written by Girolamo Frascatoro (a medical student of Copernicus), and by 1553 the disease was known by this name (ibid.).

Syphilis spread quickly across the globe. “Before long, the disease was being spread by the crew of Vasco da Gama’s ships to the people of India and Japan, where its origins were reflected in the name ‘the Portuguese sickness’” (ibid.), and “…by 1520 had reached Africa and China” (Mbogoni 2013: 25). It spread to the Pacific and Tahiti by the 18th century, where it was known as ‘the British Sickness’ (ibid.).

Factors of Disease Spread in Relation to Colonization

The examples of the spread of disease on offer here are just that, examples. To truly cover in detail instances of the spread of disease and sickness as related to colonization would require a chapter a hundred-fold as long as what is presented here.

The spread of diseases among Indigenous populations related to colonization varied, depending on many factors. These included the diseases carried by any particular colonizing force, which in turn depended on their point of origin (e.g. Spain, England, France, etc.) and their numbers, the size of the group contacted, their prior exposure to diseases as well as the overall health and demographics of the contacted group, the date of contact, and numerous other factors (Erlandson and Bartoy 1995: 156). “Epidemics are sited in time and place and configured in terms of ecology and demography, available medical knowledge, and cultural values and collective experience” (Rosenberg 2008: S4). Studies suggest:

“that native peoples most susceptible to Old World epidemic diseases were those with high population densities, who lived in relatively large sedentary communities, and participated in extensive trade networks or other types of intervillage contact [Ramenofsky 1987:162-171; Stannard 1991:523 524; Dobyns 1992]. All other factors being equal, such societies were much more likely to contract and transmit epidemic diseases than sparse populations organized in small bands having relatively limited external contacts.” (Erlandson and Bartoy 1995: 156)

Three incised caribou bone pendants with incised designs, Beothuk, ca. 1550, Newfoundland, Canada. Collected at a time when French and British colonizers were just beginning to have somewhat regular trade contact with this Indigenous group. Image: ACC1141, Musée McCord.

Once small and relatively isolated communities were contacted, they were often annihilated by disease. One such group is the Beothuk of Newfoundland, who were driven to extinction by tuberculosis and colonial violence. Contact between the Beothuk and the trans-Atlantic world began with the Vikings in 1001. But it was the French and British colonizers who began settling in Newfoundland in the early 16th century that eventually brought an end to the Beothuk. They were officially declared extinct in 1829, with the death of the last known Beothuk, Shanawdithit, from tuberculosis (Harries 2018: 225). Both tuberculosis and malaria were life-threatening problems for Native peoples. They were more of a constant threat, as opposed to epidemic illnesses which came in episodic waves.

Vessel in the form of an Underwater Panther, probably late Mississippian Tradition, 1400 – 1600. Made in the era before large-scale warfare and spread of disease would alter life in this region dramatically. Image: 17/3425, Smithsonian Institution National Museum of the American Indian

The effects of epidemics had broader impacts other than death. Though the effects of colonization and the subsequent spread of disease around the globe was and is enormous, however, the lasting impact for Indigenous and colonized peoples has not been - to borrow the words of Indigenous archaeologist Michael Wilcox - “terminal.” Indeed, Wilcox has called for the end of “terminal narratives” accounts of Indian histories that “… explain the absence, cultural death, or disappearance of Indigenous peoples” (Wilcox 2010: 11). In the responses of colonized people, even at times of the utmost violence and sickness, it is possible to see their acts of resistance and survival, such as in the example of the 17th century mourning war of the Iroquois, the primary purpose of which was restoring vitality to the depleted Iroquois Nation:

“… in the late 1670s the Iroquois, reeling from a devastating epidemic, initiated a massive mourning war. Iroquois warriors now struck out west, where they raided the Hurons, Wyandots, Illinois, and other groups, and south, where they warred against the Indians of Carolina... Iroquois leaders allied with the Susquehannocks, who had been raiding throughout the mid- Atlantic and into the lower piedmont for at least two decades. Iroquois and Susquehannock raiders now filtered into Virginia and Carolina and harassed local Indians for the next three decades. The people of the Mississippian world, already navigating through a series of chiefdom failures, disease episodes, a weakening of chiefly authority, and various other challenges, now had to contend with armed slave raiders as well.” (Ibid..: 98).

Though the spread of infectious disease through the presence of colonists varied by time and place, the mechanisms of the transfer of disease also often decided the rate of infection. The first wave of diseases, and most lethal, to spread amongst the Indigenous populations of the Americas were so-called crowd diseases, such as smallpox, measles and influenza. These spread from person to person and can survive for long periods outside their host, particularly on trade textiles, and specifically on cotton, “…cotton is significant because cloth was an important article of exchange in northwestern New Spain [and later, elsewhere in the Americas], both before and during the colonial period” (Preston 1996: 7). The next wave of diseases “…were diseases transferred by intermediate vectors such as fleas, lice, mosquitoes (i.e., zoonotic), and surface water. These plagues-malaria, yellow fever, cholera, amoebic dysentery, typhoid fever, and typhus-may remain for long periods in the host and be infective inside and outside the victim for varying periods” (ibid.).

The bigger picture perhaps, as addressed in more recent research, is that social conditions and conditions for sustenance and survival, as restructured through colonization, more than biological vulnerability, played a role in the spread of disease among Indigenous populations around the world: “Post-contact diseases were crippling not so much because indigenous people lacked immunity, but because the conditions created by European and U.S. colonialism made Native communities vulnerable” (Ostler 2020). The oppressive conditions of colonialism sometimes even manifested in a desire amongst colonists to purposely spread disease amongst Indigenous peoples. There are, for example, documented cases where colonists attempted to spread smallpox by giving infected textiles – blankets and handkerchiefs – to Native Americans with the hopes of spreading the disease.

Coat made from a Hudson’s Bay point blanket, Dene or Métis or Nehiyaw, 1875 – 1925, Canada. Though this is a late 19th or early 20th century capote (French-style coat), made from a Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) blanket, French weavers began weaving so-called ‘point’ blankets in the 17th century, and the HBC began trading blankets with Native Americans in Canada in 1670, with 60 percent of goods exchanged in the fur trade being woven blankets (Shrumm 2018). Image: M5435, Musée McCord

This was the case with the trader and militia captain William Trent, stationed at Fort Pitt in 1763. Trent wrote of giving two Delaware emissaries infected blankets and handkerchiefs with the hopes they would become infected. Later, in that same year at Fort Pitt, Sir Jeffrey Amherst, commander in chief of the British forces in North America in the early 1760s, had a written correspondence with Colonel Henry Bouquet, in which the two men wrote of spreading the disease by giving away blankets (Kelton 2018: 103 - 106). It is not clear whether these attempts helped spread the disease, but the expressed desire to do that reflects an animus that contributed to the larger conditions under which disease could spread amongst Native Americans.

Man’s headdress from a Chiefs costume, Malecite (also ‘Wolastokiyik’ or ‘Maliseet’) tribe, New Brunswick, Canada, Mid-to late 18th century. This headdress, in its use of materials, such as red-dyed wool, yellow silk ribbon, metallic gold thread, and glass beads, is reflective of their role in global trade, as well as, less directly, reflecting the sickness and disease that they would suffer after colonial contact. Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In another example reflective of the disregard for the wellbeing and medical needs of Indigenous peoples, Indian Agent John Foster of Shelburne observed that the Mi'kmaq in his agency "do not show that vitality, strength and endurance which they have been known to possess in bygone years." Foster blamed this on a "different way of living." The recent absence of "fresh fish and game [that] was [once] within their easy reach" had been replaced of necessity by an innutritious diet of "bread, tea and molasses for breakfast; tea, bread and molasses for dinner, and molasses, tea and bread for supper.” (Walls 2017: 162)

Indigenous inhabitants around the globe were and remain hugely and calamitously impacted by the spread of disease that began with the arrival of explorers and colonists. Large scale epidemics among Indigenous inhabitants of the Americas in the first centuries after the beginning of colonization resulted in a mortality rate from 30 – 100 percent of infected populations (Ramenofsky in Erlandson and Bartoy 1995: 156). In fact, so great was the loss of life in the Americas due to disease with the arrival of Europeans, that recent research indicates that the massive loss of life and resultant abandonment of human-manipulated landscapes may have resulted in increased forest cover, contributing to climate change and a temporary global cooling (Koch et al 2019).

It is also evident that it was not just the biological effects of disease, but rather the structures of colonialism that facilitated the devastating effects of disease, whereby, in many instances of the encounter between the colonizer and the colonized “…as people, already sick and further weakened by malnutrition, trauma, and exposure, succumbed to multiple pathogens” (Ostler 2020).

Museum Collections

Cheii’s Wagon, Rapheal Begay (Navajo), Hunter’s Point, AZ, 2017. Part of Begay’s series, A Vernacular Response (on view at the Maxwell Museum at the time of closing due to the covid 19 pandemic), “…which is the documentation of land and environment with respect to symbolism, perspective, and imagination reflective of the Diné way of life. One can discern the role of creativity within Navajo art and life as a strategy for survival. The Navajo cultural teaching of hozho expresses the intellectual concept of order, the emotional state of happiness, the biological condition of health and well-being, and the aesthetic dimensions of balance, harmony, and beauty.” Image: Rapheal Begay

The pairing of objects from collections within this essay is an initial attempt to begin to survey museum collections for the connection between sickness, colonialism and museum collections.

The loss of Indigenous life and changes in social organization and circumstance around the globe due to the spread of disease related to colonization, as part of the violence of colonization, has been massive. And the effects are still ongoing. Museums, whether implicitly or explicitly, purposefully or unwittingly, have been both a source of recording and documentation for this history of colinizations, as well as a constituting agent of the structures of colonialisms.

The specific relationship of how objects, particularly those related to the colonizing of Indigenous peoples, have come to be in collections is a topic that museums and those who conduct research in them have been examining for quite some time. However, this topic of the loss and transformations of life related to the spread of disease in times of colonization is a large umbrella under which many objects in anthropology museums sit, though the connection is not often made when objects are acquired, or in the records of objects, the text labels that accompany such objects in exhibitions, or in the scholarly publications about such collections. It is astonishing to recognize that often, when encountering an object or work of art in a museum collection from a colonized culture, that some of the most accomplished and beautiful things were made during some of the most devastating parts of their histories. Many of these objects were made and/or collected when death and suffering, from either disease or violence - or both, was being visited upon their families, communities, tribes, nations and selves to a degree that is hard to comprehend.

At the same time, the impulse to maintain life, and perpetuate beauty, and “aesthetic and visual sovereignty” as Rapheal Begay, Navajo artist and Public Information Officer for the Navajo Nation, recently put it in an article for the New York Times , seems a shared desire, during times of uncertainty and widespread sickness.

Author: Devorah Romanek

Bibliography

Adjaye, Joseph K. Elmina, 'The Little Europe': European Impact and Cultural Resilience. Sub-Saharan Publishers, 2018.

Alchon, Suzanne Austin. A Pest in the Land: New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective. University of New Mexico Press, 2003.

Anderson, Stuart. “Slavery, Ships and Sickness.” Gresham College, Wellcome Library, 24 Oct. 2011, www.gresham.ac.uk/lectures-and-events/slavery-ships-and-sickness.

Asch, Chris M., and George D. Musgrove. Chocolate City: a History of Race and Democracy in the Nation's Capital. UNIV OF NORTH CAROLINA P, 2019.

Beaglehole, J. C., and Joseph Banks. The 'Endeavour' Journal of Joseph Banks 1768-1771, Volume II. Angus & Robertson Ltd., 1962.

Beck, Robin A., et al. “A Road To Zacatecas: Fort San Juan And The Defenses Of Spanish La Florida.” American Antiquity, vol. 83, no. 4, 2018, pp. 577–597., doi:10.1017/aaq.2018.49.

Binnema, Ted. “‘With Tears, Shrieks, and Cowlings of Despair’: The Smallpox Epidemics of 1781 - 1782.” Alberta Formed, Alberta Transformed, edited by Michael Payne et al., University of Alberta Press, 2006, pp. 111–132.

Bladen, F. M., and Alexander Britton. Historical Records of New South Wales .. I, C. Potter, 1893.

Blanton, Dennis B. “Drought as a Factor in the Jamestown Colony, 1607–1612.” Historical Archaeology, vol. 34, no. 4, 2000, pp. 74–81., doi:10.1007/bf03374329.

Boyd, Robert. “Disease Epidemics among Indians, 1770s-1850s .” The Oregon Encyclopedia, 19 Sept. 2019, oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/disease_epidemics_1770s-1850s/#.XsV00S_Mw0o.

Boyd, Robert. The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence Introduced Infectious Diseases and Population Decline among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774-1874. UBC Press, 1999.

Boyd, Robert. The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence Introduced Infectious Diseases and Population Decline among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774-1874. UBC Press, 1999.

“Brookes Slave Ship.” Suffolk Archives, Suffolk Archives, www.suffolkarchives.co.uk/people/suffolk-men/thomas-clarkson/brookes-slave-ship/.

Buchillet, Dominique. “Colonization and Epidemic Diseases in the Upper Rio Negro Region, Brazilian Amazon (Eighteenth-Nineteenth Centuries).” Boletín De Antropología, vol. 33, no. 55, 2018, pp. 102–122., doi:10.17533/udea.boan.v33n55a06.

Call, Charles T. “As Coronavirus Hits Latin America, Expect Serious and Enduring Effects.” Brookings, Brookings, 27 Mar. 2020, www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/03/26/as-coronavirus-hits-latin-america-expect-serious-and-enduring-effects/.

Cave, Alfred A. “The Shawnee Prophet, Tecumseh, and Tippecanoe: A Case Study of Historical Myth-Making.” Journal of the Early Republic, vol. 22, no. 4, 2002, p. 637., doi:10.2307/3124761.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 22 Apr. 2020, www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “First Travel-Related Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Detected in United States.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 21 Jan. 2020, www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0121-novel-coronavirus-travel-case.html.

Chambouleyron, Rafael, et al. “ ‘Formidable Contagion’: Epidemics, Work and Recruitment in Colonial Amazonia 1660-1750.” História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos, vol. 18, no. 4, Dec. 2011, pp. 1–18.

Cook, Noble David. Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492-1650. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Daschuk, James W. Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life. University of Regina Press, 2019.

D'Costa, Krystal. “Who Are the Indigenous People That Columbus Met?” Scientific American Blog Network, Scientific American, 12 Oct. 2018, blogs.scientificamerican.com/anthropology-in-practice/who-are-the-indigenous-people-that-columbus-met/.

Denetdale, Jennifer. “Foreward.” Hardship, Greed, and Sorrow: an Officer's Photo Album of 1866 New Mexico Territory, by Devorah Romanek, University of Oklahoma Press, 2019, pp. ix-xiv.

Diamond, Jared M. Guns, Germs, and Steel: the Fates of Human Societies. W.W. Norton & Company, 2017.

Diamond, Jared. “The Arrow of Disease.” Discover Magazine, Discover Magazine, 21 May 2019, www.discovermagazine.com/health/the-arrow-of-disease.

Dowd, Mary. “What Diseases Did the Spanish Bring Into California?” Education, 21 Nov. 2017, education.seattlepi.com/diseases-did-spanish-bring-california-5725.html.

Earle, Carville. “Environment, Disease and Mortality in Early Virginia.” Journal of Historical Geography, vol. 5, no. 4, 1979, pp. 365–390., doi:10.1016/0305-7488(79)90224-x.

Earle, Carville. Geographical Inquiry and American Historical Problems. Stanford University Press, 1992.

Erlandson, Jon M., and Kevin Bartoy. “Cabrillo, the Chumash, and Old World Diseases.” Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, vol. 17, no. 2, 1995, pp. 153–173.

Ethridge, Robbie Franklyn. From Chicaza to Chickasaw: the European Invasion and the Transformation of the Mississippian World, 1540-1715. Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2013.

Evans, Richard. “Syphilis - the Great Scourge.” Microbiology Society, 21 May 2013, microbiologysociety.org/publication/past-issues/sexually-transmitted-infections-stis/article/syphilis-the-great-scourge.html.

Fenner, Frank. Smallpox: Emergence, Global Spread, and Eradication. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, 1993.

Frith, John. “Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment until Penicillin and the Debate on Its Origins.” JMVH Syphilis Its Early History and Treatment until Penicillin and the Debate on Its Origins Comments, Journal of Military and Veteran Health, 2012, jmvh.org/article/syphilis-its-early-history-and-treatment-until-penicillin-and-the-debate-on-its-origins/.

Gallagher, Daphne E., and Stephen A. Dueppen. “Recognizing Plague Epidemics in the Archaeological Record of West Africa.” Afriques, no. 09, 2018, doi:10.4000/afriques.2198.

Goldberg, Mark Allan. Conquering Sickness: Race, Health, and Colonization in the Texas Borderlands. University of Nebraska Press, 2017.

Gupta, Ruchira. “Understanding and Undoing the Legacies of Sexual Violence in India, USA and the World.” ANTYAJAA: Indian Journal of Women and Social Change, vol. 2, no. 1, 2017, pp. 1–3., doi:10.1177/2455632717742774.

Hackett, Paul. “Averting Disaster: The Hudson's Bay Company and Smallpox in Western Canada during the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, vol. 78, no. 3, 2004, pp. 575–609., doi:10.1353/bhm.2004.0119.

Halpin, Marjorie. “‘Seeing’ in Stone: Tsimshian Masking and the Twin Stone Masks.” The Tsimshian: Images of the Past, Views for the Present, edited by Margaret Seguin, UBC Press, 1993, pp. 281–308.

Harries, John. “A Beothuk Skeleton (Not) in a Glass Case.” Human Remains in Society: Curation and Exhibition in the Aftermath of Genocide and Mass-Violence., edited by Jean-Marc Dreyfus and Élisabeth Gessat-Anstett, Manchester University Press, 2018, pp. 220–248.

Harriot, Thomas, et al. A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia: of the Commodities and of the Nature and Manners of the Naturall Inhabitants. Discouered by the English Colony There Seated by Sir Richard Greinuile Knight in the Yeere 1585. Which Remained Vnder the Gouernment of Twelue Monethes, at the Speciall Charge and Direction of the Honourable Sir Walter Raleigh Knight Lord Warden of the Stanneries Who Therein Hath Beene Fauoured and Authorised by Her Maiestie and Her Letters Patents: Typis Ioannis Wecheli, Sumptibus Vero Theodori De Bry Anno MDXC. Venales Reperiuntur in Officina Sigismundi Feirabendii, 1590.

Heckenberger, Michael. “Deep History, Cultural Identities, and Ethnogenesis in the Southern Amazon.” Ethnicity in Ancient Amazonia: Reconstructing Past Identities from Archaeology, Linguistics, and Ethnohistory, edited by Alf Hornborg and Jonathan David Hill, University Press of Colorado, 2013, pp. 57–74.

Hemarajata, Peera. “Revisiting the Great Imitator: The Origin and History of Syphilis.” ASM.org, American Society for Microbiology, 17 June 2019, www.asm.org/Articles/2019/June/Revisiting-the-Great-Imitator,-Part-I-The-Origin-a.

Hidalgo, Sebastián, et al. “African Americans Struggle with Disproportionate COVID Death Toll.” National Geographic, 29 Apr. 2020, www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/04/coronavirus-disproportionately-impacts-african-americans/.

Hoover, Robert L. “Some Observations on Chumash Prehistoric Stone Effigies.” The Journal of California Anthropology, vol. 1, no. 1, 1974, pp. 33–40.

Horwitz, Luisa, et al. “Where Is the Coronavirus in Latin America?” AS/COA, 11 May 2020, www.as-coa.org/articles/where-coronavirus-latin-america.

Houston, C S, and S Houston. “The First Smallpox Epidemic on the Canadian Plains: In the Fur-Traders' Words.” The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases = Journal Canadien Des Maladies Infectieuses, Pulsus Group Inc, Mar. 2000, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2094753/.

“Infectious Diseases at the Edward Worth Library.” Treatment |, Edward Worth Library, 2020, infectiousdiseases.edwardworthlibrary.ie/syphilis/treatment/.

Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats. “Http://Www.uniteforsight.org/Global-Health-History/module2.” The Impact of Globalization on Infectious Disease Emergence and Control: Exploring the Consequences and Opportunities: Workshop Summary., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Jan. 1970, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56579/.

Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats. “Summary and Assessment.” The Impact of Globalization on Infectious Disease Emergence and Control: Exploring the Consequences and Opportunities: Workshop Summary., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 1 Jan. 1970, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56579/.

Jeune, Paul Le. Relation of What Occurred in New France in the Year 1637: Sent to the Reverend Father Provincial of the Society of Jesus ... Burrows Brothers Co., 1898.

Jones, David Shumway. Rationalizing Epidemics: Meanings and Uses of American Indian Mortality since 1600. Harvard Univ. Press, 2004.